The Open Ocean Ecosystem from Top to Bottom

Emma Williams

What is the open ocean ecosystem?

The open ocean may not be the first or even the second or third thing that comes to mind when thinking about marine ecosystems, but it is in fact the largest ecosystem on Earth. The open ocean lies beyond the continental shelf: extending from the Arctic to the Antarctic, from the surface down to the deepest parts of the ocean, and encompassing the entire water column. On a map it accounts for 64% of the ocean and 45% of the entire Earth. Thanks to the 3D habitat that water supports, this vast ecosystem encompasses 99% of the Earth’s inhabitable space.

Sun rays through the water. Photo: Emma Williams.

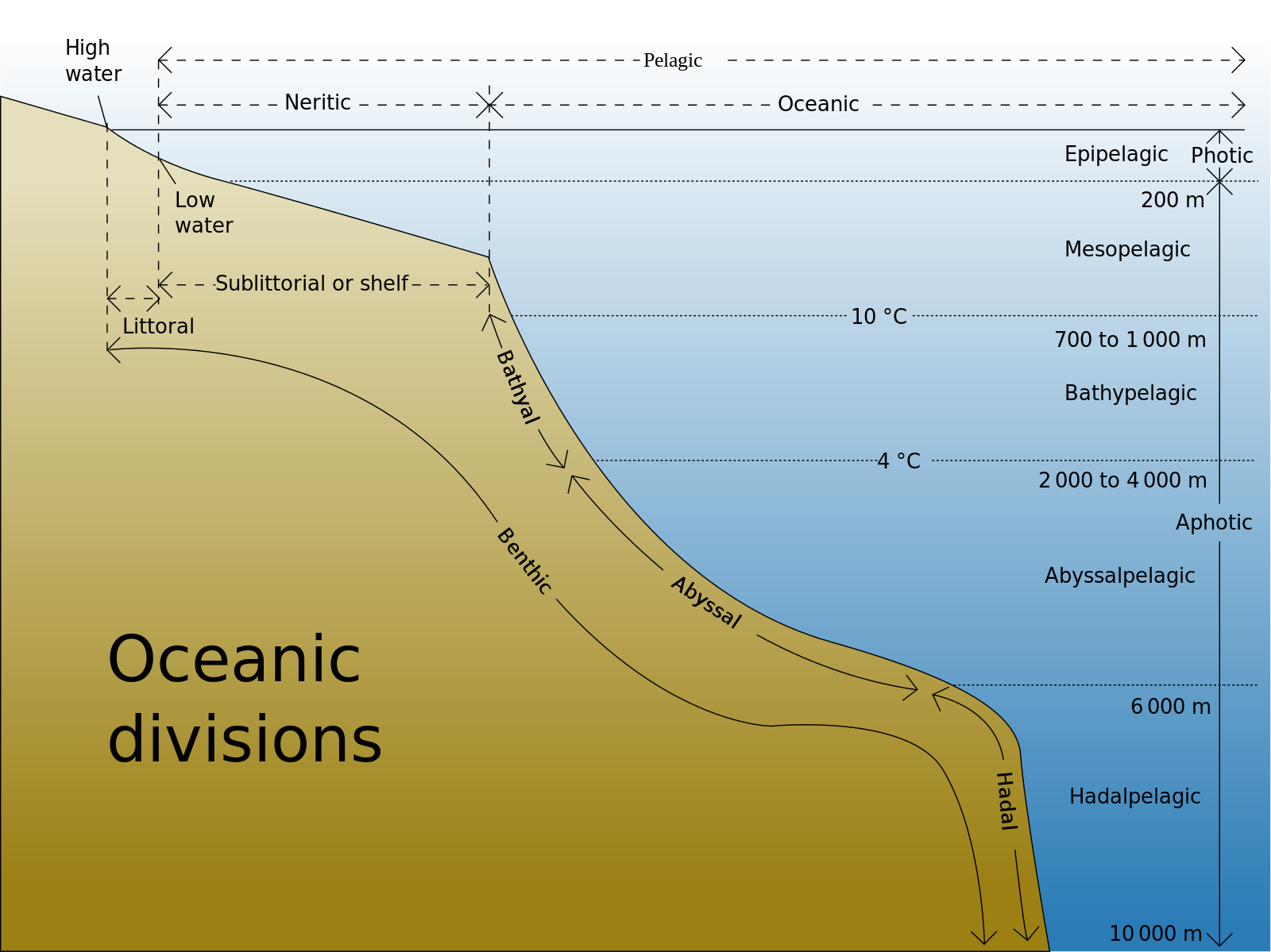

In fact, the open ocean ecosystem is so large it has been divided into five distinct zones according to depth. Each zone is characterised by different physical properties, including light availability, pressure and temperature.

The Five Zones of the open ocean:

The Epipelagic or Sunlight Zone is the area from the surface to 200m deep. Light is still able to penetrate here so photosynthesis can take place.

The Mesopelagic or Twilight Zone is the area between 200-1000m deep. Here light starts to become very limited and there is less oxygen available to the organisms that live here.

The Bathypelagic or Midnight Zone lies between 1000-4000m deep. Light is no longer able to penetrate to these depths leaving this region of the ocean in complete darkness.

The Abyssopelagic Zone extends from 4000-6000m deep, and is commonly known as The Abyss due to a lack of life found in the water column at these great depths.

The Hadopelagic Zone is characterised by deep sea canyons and trenches exceeding depths of 6000m. This includes the famous Mariana Trench which contains the deepest known point on the Earth’s surface, the Challenger Deep, with a depth of 11,034 metres.

The depth divisions zones of the ocean. Diagram: Chris Huh

How much do we really know about the open ocean?

Here’s the exciting news, more than 80% of the ocean is yet to be mapped, observed or explored. So, if you dream of exploring new lands than the water is the place to be. More people have been into space than to the depths of the open ocean. Withstanding the pressure of the deep sea makes underwater exploration extremely challenging. However, with advances in remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and submersibles we are learning more and more about the secrets and animals of our unknown blue world. The open ocean is truly an explorer’s world, with so many beautiful and bizarre animals yet to be discovered.

Which animals do live in the open ocean?

The open ocean is home to a huge array of organisms, from microscopic plankton to the largest animal to have ever lived, the blue whale, and every size, shape and spectacular creature in-between. However, life is not evenly distributed throughout the open oceans and much of it is referred to as a biological desert.

Each zone provides a different environment largely characterised by the availability of light and pressure, which in turn requires animals to have specific adaptations to be able to thrive there. Some animals are limited to certain zones due to their specific adaptations. Others are able to move between zones with relative ease, whether that’s to find prey, avoid predators, or maybe even for reproductive reasons

Spinner dolphin breaking the surface. Photo: Robin Fisher.

Tiny zooplankton undertake huge diurnal vertical migrations, actively moving from the mesopelagic zone towards the surface waters of the epipelagic zone during the night to feed, and then moving back to the depths during the day time to avoid being eaten themselves. On the flip side, sperm whales make mammoth dives holding their breath for up to 90 minutes and reaching depths of more than 1000m in search of food. At these depths sperm whales are able to find food that’s worth fighting for: the giant squid. Alongside the giant squid many other cephalopods (squid, octopus, cuttlefish and nautilus) call the deep, dark depths home, including the adorable dumbo octopus.

The deep sea truly is where the imagination can run wild. Wondrous animals found there include the Pacific barreleye fish with a rather unique transparent head, anglerfish with a light-bulb-like appendage dangling in front of their mouth ready to eat any animals inquisitive enough to investigate, and the prehistoric frilled shark which are so ancient they look more like living fossils than what most would recognise as a shark.

Jellyfish. Photo: Emma Williams.

Back up in the surface layers you can find a whole range of jellyfish varying in size and colour, the only entirely pelagic reptile the yellow-bellied sea snake which spends its entire life in open water, large pelagic fish like tuna and marlin, as well as dolphins, whales and sharks. The open ocean is also an important feeding habitat for many seabirds including penguins, albatross and puffins. Last but not least we cannot forget the vital, but sometimes overlooked, phytoplankton which forms the base of the open ocean food-webs, thus directly or indirectly supporting all other life we find there.